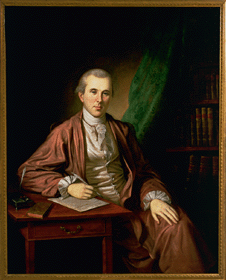

In answer to some of the student questions raised by my discussion of the state of medical practice in the 1790s, specifically as employed by Philadelphia physician Benjamin Rush, here are some answers.

In answer to some of the student questions raised by my discussion of the state of medical practice in the 1790s, specifically as employed by Philadelphia physician Benjamin Rush, here are some answers.I found an extensive discussion of the "explosively powerful" purgatives Rush used, and a picture of his medicine chest here. Calomel (a.k.a. mercury chloride) was apparently his favorite purgative. It used to be used in certain cosmetics as well as medicines, but that is illegal now. One source says it was also used for insecticides, but I imagine that is illegal now too, at least for household use.

On the amount of blood that might be drained from a patient, graduate student Roger Robinson found the following:

One typical course of medical treatment began the morning of 13 July 1824. A French sergeant was stabbed through the chest while engaged in single combat; within minutes he fainted from loss of blood. Arriving at the local hospital he was immediately bled twenty ounces (570 ml) "to prevent inflammation". During the night he was bled another 24 ounces (680 ml). Early next morning the chief surgeon bled the patient another 10 ounces (285 ml); during the next 14 hours he was bled five more times. Medical attendants thus intentionally removed more than half of the patient's normal blood supply - in addition to the initial blood loss which caused the sergeant to faint. Bleedings continued over the next several days. By 29 July the wound had become inflamed. The physician applied 32 leeches to the most sensitive part of the wound. Over the next three days there were more bleedings and a total of 40 more leeches. The sergeant recovered and was discharged on 3 October. His physician wrote that "by the large quantity of blood lost, amounting to 170 ounces [nearly eleven pints] (4.8 liters), besides that drawn by the application of leeches [perhaps another two pints] (1.1 liter), the life of the patient was preserved". By nineteenth-century standards, thirteen pints of blood taken over the space of a month was a large but not an exceptional quantity. The medical literature of the period contains many similar accounts-some successful, some not.

Delpech, M (1825). "Case of a Wound of the Right Carotid Artery". Lancet 6: 210-213.

6 comments:

I think reading about old medical methods is always very interesting. It seems from the article you linked that Dr. Rush might have been on the more extreme end of the bleed and purge school of medicine, though, and it makes more sense when you consider D'Elia's statement that "the point of medicine, like Christianity itself, was to overcome nature by means of Christ's redemptive gift and restore man to his original, perfect state."

His ideas about medicine fit the idea of a person as a machine, and are in line with the miasma school of disease that was popular at the time. The French Sergent was lucky he did not die of blood loss, and I doubt that 32 leaches on the most sensitive part of your wound is a pleasant experience for anybody.

However, history has a way of making lots of people a bit foolish. It turns out, for instance, that using radium in luminescent paint for clocks or as a food preservative is not a great idea. I would also warn against lead paint and asbestos. However, leaches can be useful when restoring the blood flow to damaged tissue, and this kind of treatment is regaining popularity in the modern medical world.

-Margaret Haden

I just think that it is interesting what doctors did back then to cure people of their ailments. At the time, they appeared to be "cutting-edge" techniques, but today they are just impractical. Such as using leaches or calomel to help people is just 1) unsafe, 2) out of date, and 3) not an effective way to treat people.

Like I mentioned earlier, people and doctors would use these treatments because they believed it would actually cure patients' problems. But in this day and age, it wouldn't work.

You could also say that 200 years from now, historians and scholars would think that practices and techniques we use to cure diseases (albeit safer than they are 200 years ago) are ineffective and out of date. It just shows how medicine has advanced the last 2 centuries and what advances medicine would make in the future.

I don't know much about the nursing field but I find Dr. Rush and his "healing" habits quite fascinating. I understand that during this time not much was known regarding the treating of people and their ailments so anything that they did would to us seem really far-fetched and in this case downright homicidal.

I don't know why he continued to do such practices unless they had worked at some point in time for him. There's no reason for him to do so unless he found them to work before and while these practices are now considered way out of date and just plain stupid I guarantee ~200 years from now doctors in the future will feel the same way about some of our current nursing practices.

Blood letting is a very interesting topic in the study of medical history. Many people today think that the practice of blood letting is archaic. This is just not true. Blood letting is still carried out in hospital across the country. Although it would most likely not be used on a stabbing victim it is still used in many other cases. The most common case of blood letting as a treatment is for Polysythemia Vera. This is a thickening of the blood and if blood letting is not conducted it can lead to stroke.

It is very interesting that so many people see blood letting as a useless practice but in fact it is still used today, with great success. I doubt today that they would drain a person of 4.8 liters over the course of a month, as the human body on average has around 5 liters of blood. This would greatly weaken a person and that French Sergeant was lucky to live. A general rule of thumb on blood loss is that a person can lose around 2 liters at a time and survive but much more is often fatal. So the fact that the doctors were letting the sergeant of a half liter at a time seems like it would be a safe practice on a healthy person.

In modern medicine we have over used antibiotics causing resistant strains of bacteria. Today's medical professionals are often looking back at historical documents to find old remedies for current problems. , They are often looking to places like China and eastern medicine. By reexamining older medical practices and applying a current knowledge base doctors are able to tweak older remedies to gain the most therapeutic effect.

Going back to what I was saying before hand, I was not staying that the practice of blood letting is not effective. I was talking more about the way it was done back in the late 1700s-early 1800s. I think that it is interesting in MeriageN's comment about blood letting for Polysythemia Vera. I did not know that.

But about my earlier comment, I was saying that we've came a long way in medical science from 200 years ago. The way that they drained blood back then would be unsafe. Medicine has improved so much in the last couple of centuries and it will get better the next two centuries.

I just wanted to clear up that I was not saying that blood letting is useless, but it is a lot safer than it use to be. That is all.

Despite his somewhat unusual practices, Rush did safe many lives during this time. If I recall correctly he helped save the life of Alexander Hamilton during the Yellow Fever epidemic of 1793. Rush would also gain a reputation for his work on mental illness.

Post a Comment